At The New Century School, with its emphasis on multilingualism, employing educators who are native speakers of a given language is critical for student success in achieving proficiency. This is not only important for measurable academic progress, it provides an undeniably special boon—TNCS becomes the setting for its own kind of rotating artist-in-residence program. This means that the artists/educators get the opportunity to experience being an educator in the United States, while TNCS students get the opportunity to learn from and with these visiting friends who bring their culture, language, and many special gifts to enhance the classroom. Federico Gauna Gonzalez embodies this beautiful synergy.

Meet “Mr Federico”

Mr. Federico wears many hats at TNCS. Originally hired as the art teacher, he now teaches art and PE to kindergarten through 8th grade students as well as Spanish to K through 4th-graders, working alongside Profé J, who teaches the 6th to 8th graders. He also helps out with aftercare.

Portrait of a Sculptor

“I’ve been doing art since I can remember.”

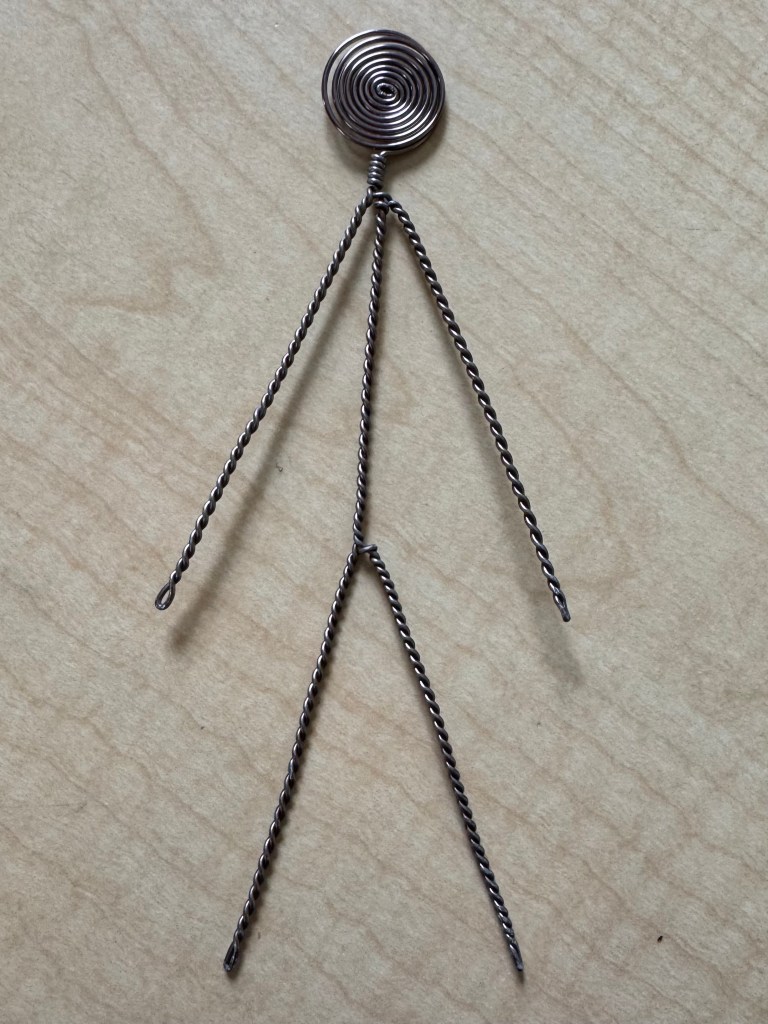

Mr. Federico was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina, but he grew up in Montevideo, Uruguay. His relationship with wire sculpture started early—at around 8 or 10 years old, an art teacher gave him a thin piece of wire during an after-school class. That moment so long ago shaped his artistic practice. He has been working with wire ever since, although he soon hopes to incorporate other materials into his sculptures.

His educational journey was exploratory and unconventional. In Uruguay, high school students specialize in their final 2 years, and Mr. Federico chose architecture. When he started university, he pursued video game design for a year and a half before realizing he wanted something closer to his wire sculpture practice. He switched to industrial design for another year and a half, but he still felt drawn to something more aligned with his artistic vision. That’s when he applied to Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA) here in Baltimore for a master’s in Fine Arts in sculpture. Remarkably—and surely a testament to Mr. Federico’s skill—MICA accepted him for a master’s degree without having completed a bachelor’s, recognizing his 3 years of diverse coursework as valuable preparation (and eager to see more of those wire sculptures).

After graduating from MICA, Mr. Federico was granted a 1-year work permit that aligned perfectly with the school year, allowing him to join TNCS. When his permit expires, he plans to return to Uruguay before pursuing another master’s degree in Europe, this time in textiles. Although this may seem like a departure from sculpture, Sr. Fedé sees it as an evolution: he’ll translate what he learns about textiles into his wire sculpture work. He also plans to continue being an educator in some fashion, having taken very naturally to this avocation.

And, with that, let’s go inside the TNCS classroom with Mr. Federico!

Teaching in Color

Mr. Federico’s day is busy and action packed. Friday’s schedule, in particular, illustrates the breadth of his responsibilities. He begins with kindergarten Spanish at 10:55, followed by planning time, then 1st to 4th grade Spanish, K- to 4th-grade art, 6th- to 8th-grade art, and finally ECAs . . . you guessed it—featuring art! It’s a packed day that spans subjects and age groups, but he describes it as “a pretty fun day.”

Art Class

Teaching art across such a wide age range requires creativity and flexibility. For kindergarten through 4th grade, a large group with varying attention spans, Mr. Federico designs one-class assignments that balance structure with creative freedom. Recently, he gave these younger students a black-and-white version of Van Gogh’s Starry Night to color however they wanted. When he showed them the original afterward, some had replicated Van Gogh’s palette while others had created entirely new interpretations. His next project will follow the same format, using a Picasso cubist painting, but this time, he won’t show them the finished product so they are nudged to experiment with their own colors and visions.

For the older students, he is about to deliver on a much-anticipated project: slime-making. While the students wanted to simply mix glue and detergent, Mr. Federico structured the activity with proper supplies, including glue, activator, food coloring, Styrofoam beads, and containers to take their creations home, transforming a quick craft into a more thoughtful, complete project.

For the older students, he is about to deliver on a much-anticipated project: slime-making. While the students wanted to simply mix glue and detergent, Mr. Federico structured the activity with proper supplies, including glue, activator, food coloring, Styrofoam beads, and containers to take their creations home, transforming a quick craft into a more thoughtful, complete project.

Indeed, his assignments are by and large products of his own imagination, a philosophy born out of remembering what it was like to be the young student stuck at a desk with a less-than-engaging task before him. He wants his students to instead be inspired, challenged, and to actually enjoy what they’re doing in class. For example, one of his smaller assignments involved puncturing holes with a pencil into a foam card to form a perforated picture or pattern. What kid wouldn’t gravitate to that assignment—sanctioned pencil punching?! The results speak for themselves.

Another involved “needlepointing” with yarn to make a picture of their own design. These kinds of structured yet unstructured activities are just what many kids need some days. They get to be productive, yet mostly unconstrained.

He adapts these types of assignments for his younger students such as be giving them more “size-appropriate” materials to work with.

But the cardboard chair project stands out as one of Mr. Federico’s most ambitious undertakings. Working in groups, the older students had to design and build a functional, full-sized cardboard chair: “Project X,” as they insisted on dubbing it. The project required sketches, a small prototype, and then the actual construction. Mr. Federico provided guidance on the properties of corrugated cardboard, such as how positioning it vertically makes it much stronger than laying it flat, but the students had to figure out the engineering themselves. Their homeroom teacher, Mr. Callahan, helped serve on the “jury” at the end. All four teams succeeded in creating chairs that could support one team member’s weight. For extra points, Mr. Federico sat on each one, and remarkably, all four held. He brought snacks from Argentina for all teams, with the winning team receiving the “best” treats, alfajores. These shortbread-type sandwich cookies are filled with dulce de leche and covered in chocolate or rolled in coconut or dusted with powder sugar. The chair that won its team the delicious alfajores is shown in the last two photos. It clearly “stands on its own.”

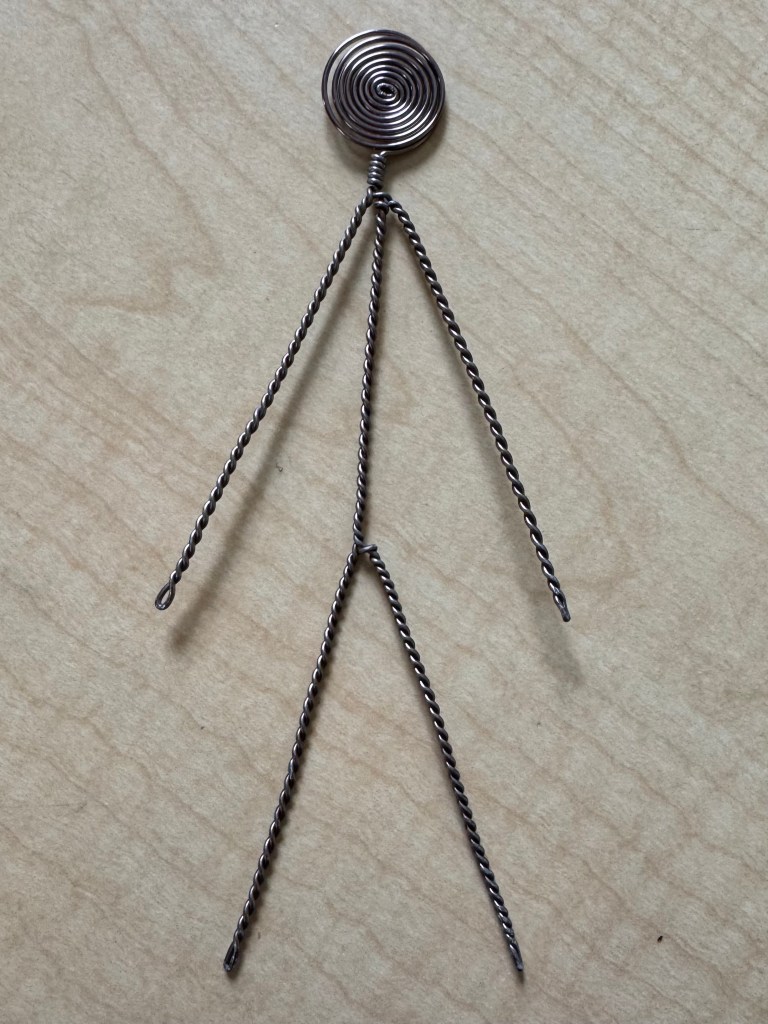

The assignment came from a first-level art class he observed during his teaching practicum at MICA, proving that even introductory college-level projects can work with younger students when properly adapted. Likewise, Mr. Federico has successfully incorporated his wire sculpture practice into his teaching. He taught the middle schoolers how to make the little wire figures that may be his hallmark. His stickmen all have spiral heads, which is compelling in so many ways. Looking at them, you can’t help but feel that headspace.

The assignment came from a first-level art class he observed during his teaching practicum at MICA, proving that even introductory college-level projects can work with younger students when properly adapted. Likewise, Mr. Federico has successfully incorporated his wire sculpture practice into his teaching. He taught the middle schoolers how to make the little wire figures that may be his hallmark. His stickmen all have spiral heads, which is compelling in so many ways. Looking at them, you can’t help but feel that headspace.

In some of his sculptures, he attaches them in intricate ways to become something else entirely. (You’ll soon see.)

While art is obviously his go-to choice of subjects to teach, Mr. Federico has come to appreciate his PE classes almost as much.

Physical Education

Mr. Federico’s camp counselor experience from high school in Uruguay prepared him well for PE duties. For several years, he worked as a camp counselor, learning how to keep large groups of children entertained and active over extended periods.

So, at TNCS, with kindergarten through 4th grade, he leads games like various forms of tag and red light, green light, although his version naturally includes creative variations like “pink light” where students must dance while walking. When the playground isn’t covered in snow, he calls out colors and students race to touch something of that color. The activities focus on movement, fun, and quick engagement. (As well as attending to visual cues—he is an artist after all.)

Middle schoolers, predictably, prefer competitive games like dodgeball or basketball, and Mr. Federico has learned to meet them where their interests lie. In fact, he joins in, much to their delight. (Just watch him walk across the TNCS campus and try to count the number of high fives and hand clasps that come his way.)

Spanish Class

“I think it’s very important, especially at a young age, to learn a lot of languages. At this age they’re like sponges and they absorb everything they learn.”

Spanish is Mr. Federico newest teaching responsibility. Although teaching Spanish per se is new to him, he was able to step right in and pick up the curriculum where the previous instructor left off. Many of the activities naturally incorporate art, such as coloring, connecting colors to names, and creating visual memory aids. Some of these types of activities he created himself, seeing how his students seemed to get the most out of them. Currently, for instance, 1st through 4th graders are learning about fruits and vegetables. They draw an example on small cards, Mr. Federico writes the names, and they play matching games to reinforce vocabulary.

Teaching kindergarteners Spanish is particularly new, as Profé J previously handled that group. Mr. Federico uses the same curriculum but simplifies the assignments, focusing more on writing fundamentals. He follows Profé J’s model of using worksheets with words to trace and repeat, incorporating seasonal themes.

Embracing the TNCS Philosophy

The approach to education at TNCS differs from what Mr. Federico experienced in Uruguay, and he appreciates this difference. The philosophy of providing structure and guidance while allowing students to explore and problem-solve independently resonates with his teaching style. The cardboard chair project exemplified this perfectly: he explained the properties of the materials and established parameters, but the students had to engineer their own solutions. He believes this approach leads to deeper learning.

The school’s multilingual curriculum also appeals to him. In Uruguay, he learned English in primary school (equivalent to 1st–6th grade) and added Portuguese in high school. He understands the value of language acquisition at a young age when children are best equipped to absorb information. The importance of multilingualism, especially when introduced early, aligns with his own educational experience and the interconnected world he navigates as an international artist.

The Artist in Baltimore and Beyond

Of course, as a bona fide fine artist Mr. Federico’s work extends beyond the classroom. He currently has sculptures displayed at the Winkel Gallery, just a block away from the school. On weekends, he can be found in Fells Point coffee shops with his wire, creating his sculptures in public spaces. Sometimes passersby ask about his work, especially when he brings his larger pieces, which can be several feet tall.

He also enjoys leaving his stickmen around Baltimore like Easter eggs for people to discover. He plans to do the same in New York during an upcoming visit. Mr. Federico also made connections with Baltimore’s existing wire sculpture community, having met the artist responsible for the clever and unexpected sculptures that hang from traffic light wires around the city. That artist is also a MICA alum.

Federico’s relationship with Baltimore evolved over time. When he first arrived and lived near MICA, he experienced the “MICA bubble”—the campus felt safe and welcoming, but stepping one block away revealed less inviting neighborhoods. After moving to the Inner Harbor, his perspective shifted. Now he walks to school every day along the water, passing boats and enjoying the waterfront. Discovering Fells Point particularly enhanced his experience. The neighborhood’s coffee shops became his creative spaces, places where he could work on his wire sculptures surrounded by the gentle hum of other people focused on their own projects, free from the distractions of home.

Over time, Baltimore grew on him. What started as a temporary stop for graduate school became a city he genuinely appreciates.

Looking Forward

Mr. Federico future unfolds in stages, each building on the last. After the school year ends, he’ll travel to Vietnam to visit a friend, potentially staying longer to pursue an artist residency in a place where the lower cost of living would allow him to focus entirely on his work without distractions.

In March, he’ll take up a 3-week artist residency in France, living in a château, devoted entirely to creating art. He plans to return to Uruguay before pursuing his textile master’s degree in Europe. Thanks to his grandfather, he holds a Spanish visa that allows him to study for free at many European institutions, potentially opening a path to living and creating there long-term.

He says teaching will likely remain part of his life, whether in Uruguay or Europe. He envisions working with older students with whom he can fully explore complex artistic ideas alongside them.

TNCS Legacy

Before leaving, Mr. Federico plans to leave TNCS one of his sculptures. He imagines it displayed near the front desk area, a permanent and uplifting reminder of the difference he makes at TNCS. The same hands that teach children to color Picasso and build cardboard chairs also create fine art everywhere they can. Like his wire sculptures, Mr. Federico’s art and his teaching are intertwined aspects of how he moves through and contributes to the world.

You can see one of Mr. Federico’s works now, hanging over the TNCS front desk.

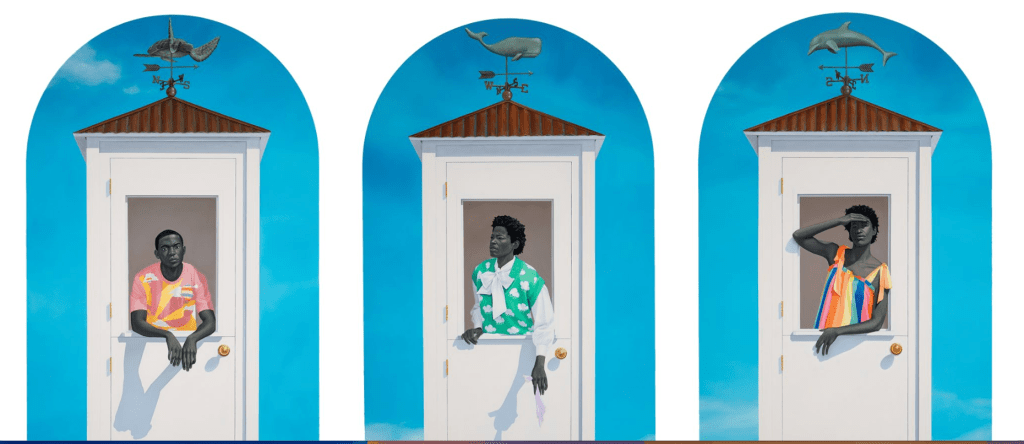

And, in a special moment that brought together many themes, TNCS Receptionist Zanyah Hawkins-Walter read excerpts from Parker Looks Up, An Extraordinary Moment, a book about a young girl’s encounter with the sublime—American Sublime, that is. It’s especially poignant when we find that what has mesmerized young Parker so completely is Sherald’s portrait of Michelle Obama, our first, First Black Lady.

And, in a special moment that brought together many themes, TNCS Receptionist Zanyah Hawkins-Walter read excerpts from Parker Looks Up, An Extraordinary Moment, a book about a young girl’s encounter with the sublime—American Sublime, that is. It’s especially poignant when we find that what has mesmerized young Parker so completely is Sherald’s portrait of Michelle Obama, our first, First Black Lady.